If you ask ChatGPT to reverse the word “Strawberry” 🍓, it often fails. Why? Is the neural network not smart enough?

The answer is actually simpler: It can’t see the letters.

Before a Large Language Model (LLM) can “think,” it must “read.” The component responsible for this is the Tokenizer. It is the invisible translator that sits between your human text and the model’s mathematical brain. Today, we will explore how this works using Andrej Karpathy’s minbpe.

1. What is a Tokenizer?

At its core, a neural network is just a giant math machine. It cannot process strings like “Hello World.” It can only process numbers.

The Tokenizer’s job is to chop text into chunks (Tokens) and assign them numbers (IDs). It effectively converts human language into a sequence of integers that the model can process.

2. Why Tokenization Matters

Before we look at how it works, we need to understand why it is so critical. As Andrej Karpathy explains in his Tokenization Lecture, tokenization is the root cause of many mysterious LLM failures.

It isn’t just a formatting step; it fundamentally constrains what the model can learn.

“A lot of the issues that may look like issues with the neural network architecture actually trace back to tokenization.” — Andrej Karpathy

Here are just a few weird behaviors caused by the tokenizer:

- Why can’t LLMs spell words? Because they often see the word as a single token (ID

502), not as a sequence of letters (L-O-L...). - Why is it bad at simple arithmetic? If the number

512is one token, but513is two tokens (5+13), the model struggles to learn consistent math rules. - Why does it glitch on strings like “SolidGoldMagikarp”? These rare strings can get chopped up in disjointed ways that the model never saw during training.

3. Visual Preview: Seeing What the Model Sees

To really “feel” the problem, let’s look at a visual example.

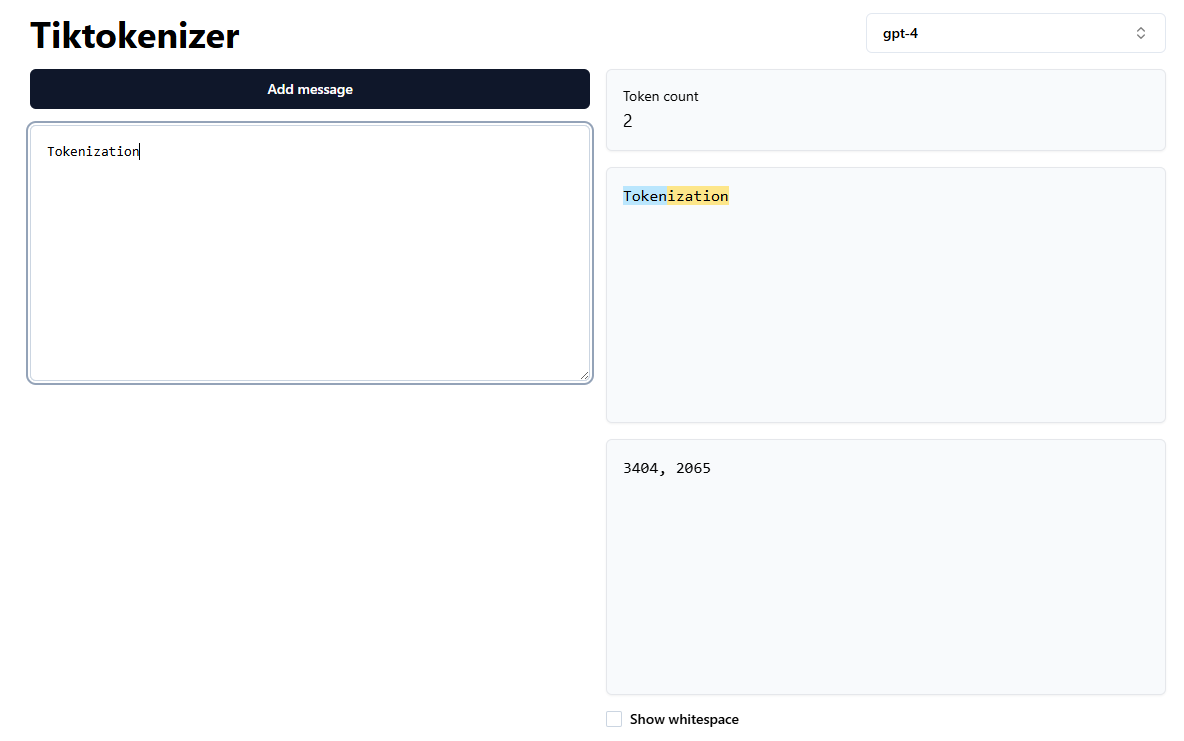

We can use the tiktokenizer webapp to run the GPT-4 tokenizer live in the browser. When you paste text into it, you don’t see words—you see colored chunks.

Example:

If we paste the word "Tokenization", it doesn’t get a single ID. It gets split:

- “Token” (ID

3404) - “ization” (ID

2065)

Watch out for spaces!

The string " is" (with a leading space) is Token 374.

The string "is" (without a space) might be a completely different token.

This “arbitrary chopping” is what the Neural Network has to deal with every time you prompt it.

4. The Goldilocks Problem

Now, the obvious question is: Why chop it like that? Why not just chop every letter?

We have three main strategies, but finding the right balance is hard:

A. Character-Level (The Microscope)

We treat every letter as a token (a=1, b=2).

- Pros: Tiny vocabulary (~100 chars).

- Cons: Too granular. The model sees “t-h-e” instead of “the.” Sequences become incredibly long and expensive to process.

B. Word-Level (The Dictionary)

We treat every full word as a token (apple=500).

- Pros: Short sequences with clear meaning.

- Cons: Too massive. English has infinite words. What about “running” vs “ran”? What about typos?

C. Sub-word Level (BPE) - The Solution

This is what modern LLMs use. We break words into meaningful chunks.

- Common words like

appleare kept whole. - Complex words like

learningmight becomelearn+ing. - Rare words are broken down into characters.

This method, called Byte Pair Encoding (BPE), gives us the efficiency of words with the flexibility of characters.

5. The Algorithm: How BPE Works

How does the Tokenizer “learn” these chunks? It doesn’t use a dictionary. It uses statistics.

The BPE algorithm iteratively merges the most frequent pair of adjacent characters.

The “minbpe” Example

Let’s see this in action using Python. Imagine our training data is just the string: "aaabdaaabac".

from minbpe import BasicTokenizer

# 1. Input Text

text = "aaabdaaabac"

# 2. Train Tokenizer

# "Start with raw bytes (256), and find the 3 best merges"

tokenizer = BasicTokenizer()

tokenizer.train(text, vocab_size=256 + 3)

# 3. See Result

print(tokenizer.encode(text))

# Output: [258, 100, 258, 97, 99]

What just happened?

- Start:

[a, a, a, b, d, a, a, a, b, a, c] - Merge 1: The pair

a, aappears most often. We merge them into a new tokenZ.- Result:

[Za, b, d, Za, b, a, c]

- Result:

- Merge 2: The pair

Z, a(aaa) appears most often. We merge them intoY.- Result:

[Y, b, d, Y, b, a, c]

- Result:

- Merge 3: The pair

Y, b(aaab) appears most often. We merge them intoX.- Result:

[X, d, X, a, c]

- Result:

The algorithm compressed 11 characters down to 5 tokens. This is how GPT-4 learned that “ing” is a useful token—it just appeared together millions of times!

6. From Integers to Meaning: The Embedding Layer

At this point, the pipeline looks like this:

Text (“Hi”) $\rightarrow$ Tokens ([“H”, “i”]) $\rightarrow$ IDs ([12, 45])

But we cannot feed 12 and 45 into the neural network yet. This is where we cross the bridge from “Discrete Integers” to “Continuous Vectors.”

The Problem with Raw Integers

You cannot feed the number “1” or “2” directly into the neural network’s equations because mathematical magnitude doesn’t apply to strings and characters (in general tokens).

Imagine you assign an integer ID to every animal in a zoo:

- Dog: 5

- Cat: 6

- Wolf: 900

- Banana: 7

If you feed these raw numbers into a neural network, the math gets confused because integers imply relationships that don’t exist:

-

Magnitude: Is a Wolf (900) “greater” than a Dog (5)? No.

-

Proximity: The integer 5 (Dog) is right next to 6 (Cat). That seems good! But… 6 (Cat) is also right next to 7 (Banana).

-

Math: If you average Dog (5) and Wolf (900), you get ~452. Is the average of a Dog and a Wolf a “Toaster” (or whatever ID 452 is)?

Conclusion: Integers are discrete and rigid. They tell you who the token is, but nothing about what it is.

To solve this, we give every token its own list of trainable numbers—a vector.

The Solution: The Embedding Table

We create a giant matrix (think of it like an Excel spreadsheet) where every row corresponds to a unique token.

In PyTorch, this is typically defined as:

# vocab_size = 65 (Rows: one for every unique token)

# n_embd = 64 (Columns: the size of the vector)

self.token_embedding_table = nn.Embedding(vocab_size, n_embd)

It is important to distinguish between the Dimensions and the Parameters:

The Dimensions (Hyperparameters): These are the settings you choose before training.

- Rows (

vocab_size): How many distinct tokens you have. - Columns (

n_embd): How much information you want to store for each token (e.g., 64, 512, or 4096 hidden numbers).

The Trainable Parameters (The “Cells”): These are the actual numbers inside the spreadsheet.

- At the start, these numbers are random values.

- Crucially: During training (backpropagation), the model tweaks these numbers so they mathematically represent the meaning of the token better.

Let’s say our n_embd is 3. We might (metaphorically) learn these three attributes:

- Is it living? (0.0 to 1.0)

- Is it furry? (0.0 to 1.0)

- Is it domestic? (0.0 to 1.0)

Now look at the vectors:

| Token | Living | Furry | Domestic | The Vector |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dog | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.90 | [0.99, 0.95, 0.90] |

| Wolf | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.05 | [0.99, 0.99, 0.05] |

| Banana | 0.95 | 0.01 | 0.50 | [0.95, 0.01, 0.50] |

Why is this better?

-

Similarity: The model can now calculate that Dog and Wolf are nearly identical mathematically, except for the last number (“Domestic”).

-

Differentiation: It immediately sees that a Banana is totally different from a Dog because the middle number (Furry) is 0.01 vs 0.95.

“Feeding” the Vector to the Model

These rows will become the trainable parameters in the Large Language Model. They are explicitly trained to capture the semantic similarity in natural language.

So, when the tokenizer outputs an ID (like 12), the corresponding row is fetched and then sent into the model. This vector (e.g., [0.1, -0.5, 0.9…]) carries the learned meaning of the token, allowing the Transformer to process concepts rather than just numbers.

If your input is ID 12:

- The model goes to Row #12 of the embedding table.

- It copies that entire row of numbers (the vector).

- This vector (e.g.,

[0.1, -0.5, 0.9...]) is what actually enters the Transformer blocks.

Summary of the Flow

$$ \text{Input: “H”} \rightarrow \text{Token ID: 12} \rightarrow \text{Embedding Lookup (Row 12)} \rightarrow \text{Vector: [0.1, -0.5, …]} $$

You no longer have a simple integer. You have a rich, multi-dimensional representation that the LLM can process, compare, and learn from.

Conclusion

The Tokenizer is the unsung hero of AI. It compresses the vast complexity of human language into a compact set of integers (BPE). Then, the Embedding Layer expands those rigid integers into rich, meaningful vectors.

The next time you chat with an AI, remember: you aren’t sending it words. You’re sending it a sequence of integers, and it’s dreaming in vectors.

References

- Code: minbpe GitHub Repository by Andrej Karpathy

- Lecture: LLM Tokenization Video (YouTube)

- Tool: Tiktokenizer (Visualizer)

- Library: Tiktoken (OpenAI’s official BPE library)

- GPT-2 Paper: Language Models are Unsupervised Multitask Learners